|

|

|

|

On Liberty ... Squashed down to read in about 35 minutes "The sole end for which mankind are warranted in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant."   Wikipedia - Wikipedia -  Full Text - Full Text -  Print Edition: ISBN 0199535736 Print Edition: ISBN 0199535736

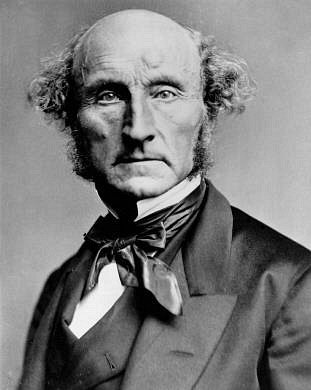

Rigorously educated by his father James Mill (the co-founder (with Jeremy Bentham) of Utilitarianism) John Stuart grew to suffer horrid depression over an upbringing which had forced classical literature, logic, political economy, history and mathematics down him before he was fourteen. He lived modestly as a clerk to the East India Company, but wrote profusely on political and philosophical matters. In Utilitarianism he states that actions are right if they bring about happiness and wrong if they bring the reverse. In On Liberty, written with his beloved wife, who died before its completion, he moved away from the Utilitarian notion that individual liberty was necessary for economic and governmental efficiency and advanced the classical defense of individual freedom as a value in itself. The basic argument is simple: that liberty is good. Good because it allows new and improved ideas to appear. Good because it forever puts the old ideas to the test and good because it just, well, is. We Europeans, thinks Mill, are so wonderful because we allow diversity of ideas, unlike the silly Chinese. Mill isn't impressed with the Chinese, or with Christians. The philosopher Fung-Yu-Lan agreed with him about China, but Mill continues to irritate religious types to this day. It is easy to pick holes in Mill's thesis. He gives lots of reasons as to how Liberty should be defended and preserved, but never actually explains why. He thinks everyone should be free, but holds that savages and children should be controlled without ever explaining what 'savages' are. He despises state control, but insists on it for certain, unspecified, 'moral' concerns. But then, there is little value in looking for a mathematics of conduct. Political philosophy is very far from a precise science, and Mr Mill's version is about as precise as it gets. No wonder then that it continues to be the model and the measure of governments the world over.

On Liberty has a reputation for being a difficult text to read. Mill is not a clear writer: he tends to expound arguments in sentences that sometimes run to a page or more before realising that he could have said it all in a couple of dozen words. It has been no easy task to pick out those prize dozens. We have been able to ditch eight words out of every nine, but retain sufficient verbiage to give a true feel of the original.

John Stuart Mill 1843 Squashed version edited by Glyn Hughes © 2011 To the beloved memory of her that was the inspirer, and in part the author - the friend and wife whose approbation was my strongest reward, and whose great thoughts and noble feelings are buried in her grave - I dedicate this volume. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTORY THE subject of this Essay is not the so-called 'Liberty of the Will', but Civil, or Social Liberty. A subject hardly ever discussed in general terms, but of profound importance. The struggle between liberty and authority is the most conspicuous feature of the history of Greece, Rome and England. But in old times liberty meant protection against the tyranny of the political rulers. They consisted of a governing One, or a governing tribe or caste, who derived their authority from inheritance or conquest. To prevent the weaker members of society from being preyed upon by innumerable vultures it was thought that there should be an animal of prey stronger than the rest. The aim of patriots was to set limits to the power of the ruler. As human affairs progressed, there came a time when what was wanted was that rulers should be identified with the people, that their interests should be the interests of the whole nation. But, like other tyrannies, the tyranny of the majority was, at first (and still commonly is) held in dread. Society as a whole can issue wrong mandates and practice a tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression. Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there also needs to be protection against the tyranny of prevailing opinion. There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence, and to find that limit is indispensable to a good condition of human affairs. The question of where to place that limit is a subject on which almost everything remains to be done. Some rules of conduct must be imposed - by either law or public opinion. No two ages, and scarcely any two countries, have decided it alike. Yet the people of any given country rarely see any difficulty, tending to assume that it is a subject on which mankind is agreed, such is the illusion of the magical power of custom. People are accustomed to believe (encouraged by some philosophers) their feelings on such subjects are better than reasons, and render reasons unnecessary. Whenever there is an ascendent class, the morality of the country emanates from its class interests - consider the Spartans and the Helots, the Negroes and the planters, men and women. Another grand principle has been the servility of mankind towards their gods. It has made men burn witches and magicians, yet remember that those who first broke away from the yoke of the so-called Universal Church were usually as unwilling to permit difference of religious opinion as that church itself. The majority have not yet learned to feel the power of the government to be their power, or its opinions their opinions. The object of this essay is to assert one simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual. That principle is that the sole end for which mankind are warranted in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign. (Despotism, however, is the legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided the end be their improvement.) In the first instance we will confine ourselves to the Liberty of Thought. CHAPTER 2: OF THE LIBERTY OF THOUGHT AND DISCUSSION Let us suppose that the government is entirely at one with the people, and never thinks of exerting coercion unless in agreement with their voice. I deny the right of the people to exercise such coercion. Such power is illegitimate, the best government has no more title to it than the worst. The particular evil of silencing the expression of opinion is that it is robbing the human race, posterity as well as the existing generation - those who dissent as well as hold the opinion. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity to exchange error for truth, if wrong they lose what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error. It is necessary to consider two hypotheses. First, that we can never be sure that the opinion we are endeavoring to stifle is a false opinion: second, if we were sure, stifling it would be an evil still. First, the opinion which it is attempted to suppress may possibly be true. Those who desire to suppress it, of course, deny its truth: but they are not infallible. The silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility, for while everyone knows himself to be fallible, few think it necessary to take any precautions against their own fallibility. Few care that it is mere accident which has decided their opinions, like the devout churchman in London, who would be a Buddhist or a Confucian in Peking. In order to illustrate the mischief of denying a hearing to opinions because we have condemned them it will be desirable to discuss a concrete case. For this, I choose, by preference, the case least favorable to me - that of a belief in God and in a future state. It is not the feeling that such a doctrine is sure which I call an assumption of infallibility, it is undertaking to decide the question for others without allowing them to hear what may be said to the contrary. Mankind can hardly be too often reminded that there was once a man called Socrates, who was put to death for denying the gods recognized by the state. Then there was the event on Calvary more than eighteen hundred years ago - the man who has left such an impression of moral grandeur that subsequent centuries have done homage to him as the Almighty in person, was ignominiously put to death, as what? As a blasphemer. Men did not merely mistake their benefactor, they took him for the exact contrary of what he was. Orthodox Christians who think that those who stoned the first martyrs must have been worse men than they themselves are ought to remember that one of those persecutors was Saint Paul. No Christian more firmly believes that atheism is false and tends to the dissolution of society than Marcus Aurellus believed the same of Christianity. The enemies of religious freedom occasionally say, with Dr Johnson, that persecution is an ordeal through which truth must pass, legal penalties being, in the end, powerless against truth. This argument is sufficiently remarkable not to be passed without notice, though I believe it is mostly confined to the sort of persons who think that new truths may have been desirable once, but that we have had enough of them now. The dictum that truth always triumphs over persecution is a pleasant falsehood which experience refutes. To speak only of religious opinions: Arnold of Brescia, Fra Dolcino, Savonarola, The Albigeois, The Lollards, The Hussites and many others were all put down before the Reformation succeeded. We do not now put to death the introducers of new opinions, but let us not flatter ourselves that we are free from legal persecution. In 1857 a Cornish man was sentenced to twenty-one months in prison for using some offensive words concerning Christianity. These are, indeed, but rags and remnants of persecution. But though we do not now inflict so much evil on those who think differently from us, it may be that we do ourselves as much evil as ever by our treatment of them. Our mere intolerance kills no one, roots out no opinions but induces men to disguise them or to abstain from any active effort to diffuse them. Second: let us assume received opinions to be true and examine in what manner they are likely to be held when their truth is not freely and openly canvassed. However unwilling a person is to admit that his opinion may be false, he ought to consider that if it is not fully and fearlessly discussed it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth. Those who know that they are right think that no good, and some harm, comes from it being allowed to be questioned. But he who know only his own side, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, but if he is unable to refute the reasons of the other side he has no grounds for preferring either opinion. Ninety-nine in a hundred 'educated men' are in this condition, even those who can fluently argue for their opinion. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know. The Catholic Church has a way of dealing with this problem. The clergy may acquaint themselves with the arguments of their opponents, in order to answer them, and may therefore read heretical books. The laity must accept opinions on trust; instead of a vivid conception of a living belief, there remains only a few phrases learned by rote. We have now recognized the necessity to the mental well being of mankind (on which all other well-being depends) of freedom of opinion, and freedom of the expression of opinion,on, on four distinct grounds: (1) If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we know, be true. To deny this is to assume infallibility. (2) Though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and commonly does, contain a portion of truth: and since the prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely the whole truth, it is only by collision of opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. (3) Even if the received opinion be the whole truth: unless it is vigorously and earnestly contested it will, by most who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. (4) The meaning of a doctrine will be in danger of being lost. Before quitting the subject of freedom of opinion it is fit to point out that opinions contrary to those commonly received can only obtain a hearing by the use of studied moderation in language and avoidance of unnecessary offense. Unmeasured vituperation really does deter people from learning contrary opinions. It is, however, obvious that law and authority have no business in controlling this, the real morality of public discussion. I am happy that many controversialists observe this, a still greater number strive toward it. CHAPTER 3: ON INDIVIDUALITY, AS ONE OF THE ELEMENTS OF WELLBEING Such are the reasons which make it imperative that human beings should be free to form and express opinions without reserve. Let us next examine whether the same reasons require that men should be free to act upon their opinions - so long as it is at their own risk and peril. The last proviso is indispensable. No one pretends that actions should be as free as opinions. An opinion that corn dealers are starvers of the poor ought to be unmolested in the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered to an excited mob assembled before the house of a corn dealer. The liberty of the individual must be thus far limited: he must not make himself a nuisance to other people. But if he refrains from molesting others in what concerns them, and merely acts according to his own inclination in things which concern himself he should be allowed to carry his opinions into practice at his own cost. While mankind are fallible, their truths only half-truths, it is useful that there should be different opinions and different experiments of living: that free scope should be given to varieties of character, short of injury to others, so that the worth of different modes of life can be proved in practice, when anyone thinks fit to try them. In maintaining this principle, the greatest difficulty is the indifference of people to the end in sight. The majority, being satisfied with the ways of mankind as they are now (for it is they who make them what they are) cannot comprehend why those ways should not be good enough for everybody. Yet it would be absurd to pretend that people should live as if nothing was known before they came into the world, it is the privilege of a human being, at maturity, each to use and interpret experience 'in their own way, to find out what part of tradition, custom or experience is properly applicable to his own circumstances. He who lets the world choose his plan of life for him has no need of any faculty other than ape-like imitation. We are assuredly but starved specimens of what nature can and will produce. Human nature is not a machine doing exactly the work prescribed for it, but like a tree which requires to grow and develop on all sides. But society has now fairly got the better of individuality: the danger which threatens humanity is not the excess, but the deficiency, of personal impulses and preferences. Even in what people do for pleasure, conformity is the first thing thought of; they exercise choice only among things commonly done: peculiarity of taste, eccentricity of conduct, are shunned equally with crimes: until human capacities are withered and starved: they become incapable of any strong wishes or native pleasures. Now is this, or is it not, the desirable condition of human nature? It is so in the Calvinist theory according to which the one great offense of man is self-will "whatever is not a duty is a sin". To one holding to this theory, crushing the human faculties is no evil: man needs no capacity but that of surrendering himself to the alleged will of God. In proportion to the development of his individuality, each person becomes more valuable to himself, and is therefore capable of being more valuable to others. It is essential that different persons be allowed to lead different lives - even despotism does not produce its worst effects so long as individuality exists under it: and whatever crushes individuality is despotism, by whatever name it be called, whether it professes to be enforcing the will of God or the injunctions of men. For what more or better can be said of any condition of human affairs than that it brings human beings themselves nearer to the best that they can be. However, these considerations will not convince those who most need convincing - it is necessary to show that developed human beings are of some use to the undeveloped- to point out to those who do not desire liberty that they may in some manner be rewarded for allowing other people to make use of it without hinderance. In the first place, I suggest that they might possibly learn something from them. There is always need of persons to discover new truths, to commence new practices. These few are the salt of the earth. Persons of genius, it is true, are always likely to be a small minority: but in order to have them it is necessary to preserve the soil in which they grow. Genius can only breathe freely in an atmosphere of freedom. Persons of genius are by definition [ex vi termini] more individual than other people- less capable of fitting into any of the small number of moulds which society provides. Originality is the one thing which unoriginal minds cannot feel the use of. If they could see what it could do for them it would not be originality. The first service which originality has to render them, is to open their eyes. In this age the mere example of non-conformity, the mere refusal to bend the knee to custom, is itself a service. Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric. Eccentricity has always abounded when and where strength of character has abounded; and the amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigor, and moral courage which it contained. That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of the time. Nothing was ever done which someone was not first to do, and all good things which exist are the fruits of originality. In sober truth the general tendency of mankind is to mediocrity. At present, individuals are lost in the crowd. Public opinion rules the world, though not always the same sort of public. In America it is the whole white population: in England the middle class. But they are always a mass, a collective mediocrity. The general average of mankind are moderate in intellect and inclinations, they have no tastes or wishes strong enough to incline them to do anything unusual, and consequently do not understand those who have, and class all such with the wild and intemperate. The popular idea of character is to be without any marked character- to maim by compression like a Chinese lady's foot. Much of the world has, properly speaking, no history because the despotism of Custom is complete. We have as a warning example China- a nation of much talent and wisdom who ought to have kept themselves at the head of the development of the world. Yet they have become stationary, and if they are to be improved it must be by foreigners. A people, it appears, may be progressive for a certain length of time, and then stop: when does it stop? When it ceases to possess individuality. What is it that has preserved Europe from this lot? What has made the European family of nations an improving, instead of a stationary, portion of mankind? Not any superior excellence in themselves, but their remarkable diversity of character and culture, their striking out in such a variety of paths. CHAPTER 4: OF THE LIMITS TO THE AUTHORITY OF SOCIETY OVER THE INDIVIDUAL What then is the rightful limit to the sovereignty of the individual over himself? How much of human life should be assigned to individuality, and how much to society? To individuality should belong the part of life in which the individual is interested: to society, the part which chiefly interests society. Though society is not founded on a contract, everyone who receives the protection of society owes a return for the benefit. It would be a great misunderstanding of this doctrine to suppose that it is one of selfish indifference about the well-being of others. There is need of a great increase of exertion to promote the good of others, but benevolence can find other instruments than whips and scourges, either of the literal or metaphorical sort. I do not mean that our feelings toward others should not be affected by their self-regarding qualities. A person who shows rashness, obstinacy, self-conceit- who cannot live within moderate means or who pursues animal pleasures at the expense of those of feeling and intellect must expect to be lowered in the opinion of others. We are not bound to seek his society: we have a right to avoid it and a right, maybe a duty, to caution others against him. If he displeases us, we may express our distaste: but we shall not feel called upon to make his life uncomfortable. If he has spoiled his life by mismanagement, we shall not, for that reason, desire to spoil it still further. The distinction here between the part of a person's life which concerns only himself and that which concerns others, many will refuse to admit. How can the conduct of a member of society be a matter of indifference to the rest of society? No person is entirely isolated. If he injures his property, he does harm to those who derived support from it. If he deteriorates his bodily faculties, he becomes a burden on others. Even if his follies do no direct harm to others, he is nevertheless injurious by example. If protection against themselves is due to children, is not society equally bound to afford it to those mature persons who are incapable of self-government? If gambling, drunkenness or idleness are injurious to happiness, why should the law not repress them? There is no question here about restricting individuality. The only things it is sought to prevent are things which have been tried and condemned from the beginning of the world. So no person should be punished for being drunk: but a soldier or policeman should be punished for being drunk on duty. Whenever, in short, there is a definite damage, or risk of damage, either to an individual or the public, the case is out of the provenance of liberty and placed in that of morality or law. But the strongest argument against public interference with personal conduct is that when it does interfere, the odds are that it interferes wrongly. There are many who consider as an injury to themselves any conduct they have a distaste for- like the religious bigot when charged with disregarding the religious feelings of others has been known to retort that they disregard his feelings by persisting in their abominable worship. Examples will show that this principle is of serious and practical moment. Nothing in the creed of Christians does more to envenom hatred of the Mohammedans than their practice of eating pork, which they think to be forbidden and abhorred by the Deity. But to forbid the eating of pork, even in a Mohammedan country would be interfering with the personal tastes of individuals. The majority of Spaniards think it a gross impiety to worship the Supreme Being in any other than the Roman Catholic manner- so no other worship is lawful on Spanish soil. Wherever the Puritans have been powerful, as in New England or in Great Britain at the time of the Commonwealth, they have endeavored to put down all public amusements: especially music, dancing, games and the theater. Under the name of preventing intemperance, the people of one English colony and nearly half the United States have been interdicted by law from making any use whatever of fermented drinks. The claim is that "strong drink destroys my primary right of security by creating social disorder" A theory of "social rights" like this says that 'it is the right of every individual to require every other individual to act as he ought' Another example: Without doubt, abstinence from work on one day each week is a highly beneficial custom, and might even be right to be guaranteed by law. But the restriction of Sunday amusements can be defended on no other ground than that they are religiously wrong- a motive of legislation which must be protested against "Deorum injuriae Diis curae" [Injustices to the gods are the concern of the gods] Polygamy: permitted to Mohammedans, Hindus and Chinese seems to excite unquenchable animosity when practiced by persons who speak English and profess to be a kind of Christians- the Mormons. Let them send missionaries if they please, but I am not aware that any community has a right to force another to be civilized. So long as the sufferers from a bad law do not ask for assistance, I cannot admit that persons entirely unconnected with them have any right to step in. CHAPTER 5: APPLICATIONS I now offer not so much applications as specimens of applications which may serve to bring into greater clearness the principles asserted in these pages. The maxims being followed are: (1) The individual is not accountable to society for his actions in so far as these concern the interests of no person but himself. (2) The individual is accountable for such actions as are prejudicial to the interests of others, and may be subject to social or legal punishment if society is of the opinion that this is necessary for its protection. In many cases the individual pursuing a legitimate object necessarily causes pain or loss to others. Whoever succeeds in an overcrowded profession or in competitive examinations reaps benefit from the loss of others. But, by common admission, society admits no right to the disappointed competitors to immunity from this kind of suffering, and feels called to interfere only when means of success contrary to the general interest have been employed- namely fraud, force or treachery. Trade is a social act. It is now recognized, though not till after a long struggle, that both the cheapness and good quality of commodities are most effectually provided for by leaving the producers and sellers perfectly and equally free. This is the doctrine of 'free-trade'. As the principle of individual liberty is not involved in the doctrine of free trade, so neither is it in most of the questions which arise respecting the limits of that doctrine, as for example what amount of public control is admissible for the prevention of fraud by adulteration, or to protect the safety of work people. The example of the sale of poisons opens the question of how far liberty may be invaded for the prevention of crimes or accidents. A person may interfere to prevent a crime before it happens. If anyone saw a person attempting to cross an unsafe bridge, with no time to warn him of the danger, they might seize him and turn him back. Nevertheless (unless he be a child, or not of full mind) he ought, I conceive, only be warned of the danger, not forcibly prevented from exposing himself to it. With the sale of poisons- labeling it as dangerous can be enforced without violation of liberty. But to require, in all cases, the certificate of a medical practitioner would make it sometimes impossible or expensive to obtain the article for legitimate use. The only way, apparent to me, consists of providing what Bentham called 'preappointed evidence', for the seller to record details of the purchaser and the transaction. The right of society to ward off crimes against itself suggests a limitation to the maxim that self-regarding conduct cannot be meddled with. Drunkenness, for example, is not a fit subject for legislative interference, but I consider it perfectly legitimate that a person who had once been convicted of an act of violence to others under the influence of drink should be placed under a special restriction. So again, idleness (except in a person receiving public support, or when it constitutes a breach of contract) cannot without tyranny be made a subject of legal punishment: but if due to idleness a man fails to, for instance, support his children, it is no tyranny to force him to fulfil that obligation by compulsory labor, if no other means are available. Again, there are acts which, being directly injurious only to the agents themselves ought not to be prevented, but which if done publicly, are a violation of good manners and, as offenses against others may be rightly prohibited. Of this kind are offenses against decency: on which it is unnecessary to dwell. All persons should be free to assemble in each other's houses- yet public gambling houses should not be permitted. It is true that the prohibition is never effectual: but they may be compelled to conduct their operations with secrecy, so that only those who seek them know anything about them. Should the state render the means of drunkenness more costly? To tax stimulants for the sole purpose of making them more difficult to obtain differs only in degree from their entire prohibition, and would be justifiable only if that were justifiable. But taxation for fiscal purposes is inevitable, so to tax stimulants up to the point which produces the largest revenue is not only admissible, but is to be approved of. Any further restriction I do not conceive to be justified- the limitation in number of beer and spirit houses is suited only to a state of society in which the laboring classes are avowedly treated as children or savages. It was pointed out early in this essay that the liberty of the individual in things which wherein the individual is alone concerned, implies a corresponding liberty in any number of individuals to regulate jointly the things which concern only themselves. However, an arrangement by which someone sells themselves as a slave would be null and void as he would defeat his own case for liberty. The principle of freedom cannot require that he should be free not to be free. Baron Von Humboldt states that engagements which involve personal relations or services should never be legally binding beyond a certain duration of time- and that the most important of these, marriage, should be dissolvable by nothing more than the declared will of the parties. The present almost despotic power of husbands over wives need hardly be enlarged upon here. It is the case with children that misapplied notions of liberty see a man's children as almost mere extensions of himself. Surely after summoning a human into the world it is a duty to give that child a fitting education, to fail to do so is a moral crime against both the unfortunate offspring and against society. Yet scarcely anyone in this country will hear of obliging parents to achieve this. An instrument for performing this could be no other than public examinations, beginning at an early age. Every child must be examined to see if he (or she) is able to read. If unable, the father might be subject to a moderate fine, to be worked out, if necessary, by his labor. To prevent the state from exercising improper influence over opinion, the knowledge tested in examinations should be confined to facts and positive science exclusively, though there should be nothing to hinder children from being taught religion, if their parents choose. Higher examinations should be voluntary, granted to all who pass the exam and conferring no authority other than that granted by public opinion. Laws on the Continent which forbid marriage unless the parties can show that they have means to support a family are not objectionable as violations of liberty. Objections to government interference (when it does not infringe liberty) are of three kinds: (1) When a thing is better done by individuals than by government. Generally there are none so fit to conduct any business as those who are personally interested in it. (2) Even if individuals do not do things so well, it is better to let them take care of their own affairs in, for instance, jury trials, industrial and philanthropic organizations, voluntary associations, allowing each to learn from the experiments of others. (3) The most cogent reason is to prevent the evil of too great a power. If roads, railways and companies all became departments of central administration then not all the freedom of the press or a popular legislature would make the country free in any but name. Where people are accustomed to expect everything to be done by the state, they hold the state responsible for all evil which befalls them. Should the evil exceed their patience, they make revolution- whereupon someone else, with or without legitimate authority, vaults into the seat and all continues much as before. The central organ should have a right to know all that is done, and a duty to disseminate that knowledge- but limited to compelling local officers to obey the law. Like the Poor Law Boards superintending the administrators of the Poor Rate, such powers as the Board exercises are for the cure of maladministration in matters affecting the wider community, for no locality has a moral right to make itself a nest of pauperism overflowing into neighboring communities to impair their moral and physical condition. The worth of the state is the worth of the individuals comprising it. A state which dwarfs its men will find that with small men no great thing can be accomplished.  John Stuart Mill 1806-1873 The grave of John Stuart and Harriet Taylor Mill Cimetiere St. Veran, Avignon, Vaucluse, France  ISBN 9781326806781 |